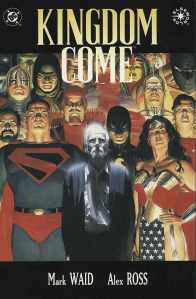

MICHAEL A. VENTRELLA: I’m very pleased to be interviewing Mark Waid, one of the biggest names in comics today. He’s been an editor with DC and as a freelance writer has become one of the most well-known and prolific writers of quality comics. In 1996, with artist Alex Ross, he released his best-known work, the graphic novel KINGDOM COME, which depicted the fate of Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman and other heroes as the world around them changed. Its popularity led to him receiving the Comics Buyer’s Guide Award for Favorite Writer in 1997. He has since gone on to fame with the FANTASTIC FOUR and with the re-imagining of Superman’s origins in BIRTHRIGHT. Currently he is an editor-in-chief with Boom! Studios and has been writing for THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN, including one of my favorite books in which Spider-Man saves Stephen Colbert. (You can see it on the shelves behind Stephen if you watch the show).  His web page is here.

His web page is here.

Mark is also the only big name in comics who I’ve known since High School, who was in my Dungeons and Dragons group in college, and who went to my wedding. It’s always great to see a good friend make it big in a job he loves! Mark is a true Superman purist, and I still recall leaving the theater with him after watching “Superman 2”, hearing him curse because “Zod shouldn’t have had that stupid power to point his finger at someone and make them float into the air!”

MARK WAID: It’s true. I’m still traumatized, by the way. At least the recently released Richard Donner cut finally set my mind at ease. But don’t get me started on Superman IV.

VENTRELLA: Mark, writing for graphic novels involves a different type of writing skill than would be needed for a short story or novel, but still requires a mastery of words. What is your creative process?

WAID: As an incredibly general rule, for me, every story springs from images. As I tell young writers who are breaking into comics, you don’t have to tell super-hero stories–comics is a wide medium that covers all genres–but for the love of God, it’s a visual medium, so it’s not the best fit for your J.D. Salinger riff or the extended inner-monologue. The short rule of thumb is that, in comics, you should take advantage of your unlimited visual budget and shouldn’t waste a lot of space on talky plainclothes scenes unless they’re visually interesting in and of themselves. Use the medium to its fullest. Tell a story that couldn’t be told just in dialogue or in prose or in iambic pentameter.

And be aware that comics is a collaborative medium, so don’t fall into the trap of thinking it’s all about dialogue. It ain’t a Mamet play. It’s words and pictures together, in concert.

For me, I’ll start thinking about the characters I’m writing about–whether of my own invention or established characters like Superman or Spider-Man–and, with a very general idea of the sort of story I want to tell or the sorts of character beats I want to hit, I’ll let my mind wander until I hit an idea for a scene that has impact. (“Hmmm…I want to write a story about Spider-Man’s enemy, Electro, having lost all his stolen-but-invested money in the same economic crash that’s recently ruined so many honest lives–and how a very powerful villain who feels he’s been robbed would react to the idea of government bailouts. Huh. I should have him stage a scene at the New York Stock Exchange. He can rant and rave like Rick Santelli, but with electrical bolts coming off of him, stronger and more chaotic as he gets more and more worked up, NYSE monitors exploding around him.”)

Once I come up with three or four of those scenes, I start to knit them together in my head to form a narrative, tossing out (or, more likely, saving in the S.O.S. file [Some Other Story]) the scenes that don’t support the tale.

Then it’s creating a rough outline or beat-sheet for a story, with a 1000-stories-under-my-belt sort of instinctive feel for how many pages to allot each scene (knowing that, in the actual writing, they ALWAYS take up more room than allotted). Then the hard part: typing “Page One, Panel One” and going from there.

But, as I say, it’s about conveying your ideas visually as well as verbally. The entire working process hinges on being able to do that.

VENTRELLA: Do you find yourself limited in that you primarily are writing for established characters?

WAID: Not really. Honestly, there are trade-offs. No, I can’t have Superman or Batman do anything I want them to do given that I don’t own them, but at the same time, having grown up reading the adventures of these established characters as a fan, what they do and don’t do is burned into my DNA. In that sense, I don’t find writing for them any more limiting than I do being behind the wheel of a car that I can’t make fly. It’s not like I drive around feeling “limited.” I just feel like I’m working with a familiar tool and automatically know what it can and can’t do.

On the other hand, when I write my own characters in series that I own, all limitations are off–but that’s as daunting as it is freeing, because there are more decisions to make as a writer, and the freedom that brings is counterbalanced by the sometimes paralyzing number of choices literally at my fingertips.

VENTRELLA: Do space considerations stand in your way?

WAID: Always. Constantly. Always. Always. Oh, God, how I envy screenwriters. You need an extra page, Mr. Movie Writer? Take an extra page. American mainstream comics, on the other hand, are generally about 22 pages long, give or take, and if you’re doing a story that’s in one installment, you have to fit it to that space. If you’re doing a longer story that spans several issues, you still have to construct each individual issue with some sense of climax/resolution or obstacle/victory or what have you in order for the reader to enjoy each issue as it comes. Honestly, most of the storytelling choices I make on a daily basis have less to do with plot and character than then do with trying to figure out how to fit those things into this rigid structure. It’s like writing haiku.

And even if you’re setting out to do a longer-form graphic novel, space is still a consideration. Only so much art will fit on a page. Only so many words will fit comfortably within each panel without crowding out the art. AND your job as a writer is to try to convey information as economically as possible without sacrificing plot or character, so there’s that plate to juggle, too; again, even when you’re working longer-form, real estate is precious. Each panel of a comic story is a “frozen moment,” a snapshot from your story, and only so many can fit.

I go into excruciating detail on these points on my blog, markwaid.com, which is full of craft essays. And because I’m not always sober when I write them, they’re probably more entertaining than this answer has been.

VENTRELLA: Do you ever plan on writing a novel?

WAID: Dear Jesus God, no. Never. I don’t have the attention span for it, I don’t have the linguistic chops, and I don’t have time to teach myself without starving to death. I am endlessly appreciative of writers who have that level of vision or that work ethic, but the few times I’ve tried my hand at prose (a Superman short story and The Flash: The Life of Barry Allen), it nearly killed me.

VENTRELLA: How has being an editor helped your writing?

WAID: Being an editor before I was a full-time writer was the greatest career boon you can envision. At DC, I edited several scripts a month from, eventually, every major and minor writer in the medium at that time, including Neil Gaiman, Grant Morrison, and others. Reading their scripts and constantly observing how they solved storytelling problems was like boot camp. I learned more in those two years as an editor than I could have in ten years as a writer.

VENTRELLA: What is the biggest mistake you see young writers making? And what was your biggest career mistake?

WAID: Without fail, young writers give me scripts that are far too dense. I’m sorry, but you cannot fit a shot of a baseball stadium interior, a supermarket parking lot crowd of 200, and an establishing shot of downtown Tokyo all on one page and still have room for fourteen captions, six balloons, and three close-ups. They don’t picture in their own heads what they’re describing, or else their heads would explode. Even someone with no art training should be able to realize that you can’t show an Olympic swimming event AND the gold crown on a swimmer’s tooth all in the same image.

My biggest career mistake? How long to you expect me to keep typing here? This could go on a while, but to pick one at random: I should have written less so I could have written it better. Early on, I did the whole panicked-freelancer thing and took on as much work as I could handle only on my very best, most productive weeks–and, in doing so, churned out more than a few clunkers. Looking back, I wish I’d always taken one less assignment than common sense would tell me I could handle. My wallet might not have been as full, but my batting average would be higher because I wouldn’t have been swinging at every pitch.

VENTRELLA: To balance that last question, what was your best career decision?

WAID: Never, ever, ever, ever taking a job for the money. Well, okay, once . Okay, twice. But only twice. And both times, the money was never as much as promised, and both times, I turned out esthetically indefensible work despite how hard I tried to convince myself at the time that it was good. So, lesson learned. Never hack.

VENTRELLA: Since you’ve established quite a name for yourself, do you pitch ideas now or do they come to you?

WAID: The advantage of being Editor-In-Chief at my own comics company is that I have a launch pad for all my new ideas and don’t have to “sell” them to anyone other than the readers. That’s huge for me. And for non-BOOM! Studios projects, I’m lucky enough now that, after all these years, I’m approached on things far more often than I have to do the approaching. But I’ll never take that for granted; the Comics Old Folks’ Home is still full of writers who were kings in their day and now can’t get phone calls returned.

VENTRELLA: How important is finding an agent in your field?

WAID: Almost negligible. Publishers deal with some agents who rep handfuls of artists, mostly overseas guys who need a point man who can speak English, but domestically, it’s not important. It’s good to have a lawyer who can look over contracts for you, but frankly, there’s still not enough money to be made in comics to make an agent career worthwhile.

VENTRELLA: In some ways, you’ve achieved geek power most of us only dream about: to make a very good living doing what you love. (I tried that with LARPing; didn’t work.) What do you think separates the Successful from the Wannabes?

WAID: Like I want to tell all the Wannabes. I don’t need the competition. But seriously…I’ve talked about this a lot in lectures, and I think much of it has to do with fearlessness. The reason so many aspiring creators have so many three-quarters-finished fantasy novels or film scripts perpetually on their hard drives is because they’re stuck on their stories. And the reason they’re stuck, frozen, isn’t because of anything as esoteric as “fear of success”…it’s because they’re afraid of the truth: that they screwed up somewhere earlier in the work, made some choice that didn’t work, and now in order to go forward, they’re gonna have to screw up the courage to tear up the floorboards and “unwrite” days’ or weeks’ worth of work in order to backtrack to the problem. That sucks. That’s the worst part of writing. Anyone who’s ever put together a piece of Ikea furniture and gotten to stage 47 only to realize with a sickening wave of horror that they screwed up stage 3 and have to go back…they know that feeling. It SUCKS. But the successful get out their crowbars and attack the problem. The wannabes are afraid of throwing stuff away.

VENTRELLA: As someone who is going through a vigorous editing process on my second novel, I know exactly what you’re talking about! Huge sections of my first novel were tossed aside before I even submitted it as well. It’s not fun, but necessary.

Of your work, what are you most proud of? What would you like to be remembered for?

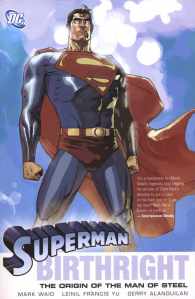

WAID: At the moment, I’m proudest of two things. I’m proud of SUPERMAN: BIRTHRIGHT, the graphic-novel that was commissioned by DC as the “definitive” origin of Superman for the 21st century, because it’s just flat-out the best thing I’ve ever written and said everything about Superman I’ve wanted to say for thirty years.

But I’m equally proud of my first issue of FANTASTIC FOUR, because on a pure-craft level, it’s a pretty good capsule of what One Good Stand-Alone Issue Of A Comic Should Read Like.

VENTRELLA: And what would you most like to see buried far away?

WAID: There’s not a landfill big enough. One of the two aforementioned jobs I took for money–1996’s SPIDER-MAN TEAM-UP #1 Co-Starring The X-Men–is still an unreadable mess.

VENTRELLA: Have to ask: Knowing how much you love the original, what do you think of “Superman Returns”? What’s your opinion on the current crop of movies based on comics and graphic novels?

WAID: Being a minority of one, I liked “Superman Returns.” I can see its flaws, but it truly was like Bryan Singer was making a movie specifically for me.

And c’mon…tell me “Iron Man” and “Dark Knight” didn’t raise the bar on comics-based movies! Like any film in any genre, there’ll be good ones and bad ones…but I’m thrilled that, in my lifetime, I get to see comics-sourced movies that are taken “seriously.”

VENTRELLA: Couldn’t agree more on those two; “Dark Knight” being my favorite film last year!

And finally: Did you meet Colbert?

WAID: NO! I was robbed. But it still warms my heart to see that something I wrote is hanging on his wall of fame as it’s in almost every show!

Filed under: writing | Tagged: agents, Comic book writing, Fantastic Four, Mark Waid, Spider-Man, Superman |

Finally! Someone who agrees on Superman Returns! My respect and appreciation for Mark Waid climbs even higher.

LikeLike